Introduction to Starting a Reef Tank

By Eric Borneman

Chief Coral Scientist

Introduction

There exists no single “recipe” for success in starting and establishing a reef aquarium and there is no way to summarize the entire cumulative knowledge and experience of millions of aquarists over three decades of captive reef husbandry. There are too many variables inherent in the process for any two tanks, begun at the same time, even with identical equipment and techniques, to both establish and mature in the same (much less predictable) way. There are, however, basic premises based on decades of common experiences along with principles of biology, chemistry, ecology, physics and biochemistry that can be exploited to maximize the probability of starting a reef aquarium that thrives over many years while minimizing the many errors and problematic issues that almost invariably occur and frequently plague aquarists over time and around the globe. I used a quote by The Offspring over twenty years ago in my book, Aquarium Corals: Selection, Husbandry and Natural History (the lead singer, Dexter Holland, incidentally...and lest the wisdom of the quote be cast aside as a mere lyric from a punk/ska band... went on to get a Ph.D in molecular biology) bears expanding and repeating here from their song, The Meaning of Life, as it almost perfectly maps the reef aquarium community:

On the way trying to get where I'd like to stay, I'm always feeling steered away by someone trying to tell me what to say and do.

I don't want it; I gotta go find my own way, gotta go make my own mistakes.

Sorry, man, for feeling the way I do….

By the way, I know your path has been tried and so it may seem like the way to go;

Me, I'd rather be found trying something new.

And the bottom line in all of this seems to say there's no right and wrong way

Starting Smart, Minimizing Mistakes, and Trying to Find “The Right Way”:

Building a Reef Aquarium

It takes time to make a “coral reef” in a tank. Aquariums go through microbial and algal cycles before becoming stable or “established.” Initially, bacteria in the water have to build up to the point where they can remove waste from the water. The bacteria that ultimately remove toxic ammonia and nitrite ions from the water are not in the water – for the most part – but grow on surfaces. In a reef tank, this is predominantly where the most surface area exists – the rock, the sand, the insides of glass and plumbing, and in filtration apparatus. There are plenty of products that contain bacteria that can ne used to “kickstart” the nitrification cycle, but all that’s needed is food. Before any corals, fish or invertebrates are purchased, a tank with water, rock and sand should be fed as though it had purchased livestock in it. The introduction of any organic material will lead to the growth of the many nitrifying bacteria that allow for the water to support purchased livestock. In fact, by simply feeding the tank as one would if livestock were present will closely allow for the population of nitrifying bacteria to approximate those required to process the regular input of nutrients once livestock are present and will limit any temporary increases to nutrient levels in the tank upon the introduction of new additions.

Coupled with nitrifying bacteria are, among other important microbial communities and their important roles in the microbiome of the tank and even individual species, are denitrifying bacteria. The process of denitrification is arguably more important than nitrification because of the need to provide nutrients in the form of foods and process the waste of livestock once introduced while concomitantly not deleteriously impacting water quality, especially in terms of nitrates and phosphates. Of course, proper filtration of an aquarium can play the predominant part of nutrient management in aquariums, but often filtration, especially flosses and filter socks, can also act as a source of undesirable nutrients by trapping organic debris (detritus, uneaten food, algae) and breaking it down into soluble nitrate and phosphates more rapidly than they can be removed because of the efficiency of microbial processes.

In terms of the filtration capacities of live rock and sand, dentrification occurs within the top few centimeters of a fine grained sands’ surface. Better fined-grained sand is called “oolitic,” meaning round rock. It is mostly available from the Bahamas and consists mainly of the aragonite (limestone) tests (shells) of tiny organisms called foraminiferans. This fine sand provides good stratification for both nitrification and denitrification to be closely coupled both physically and chemically and the smooth edges of the grains allows it to become quickly populated with many types of worms, crustaceans, and algae that all play functional roles in processing waste and detritus as well as increasing biodiversity that stabilizes the reef aquarium a a whole by providing overlapping functional groups.

Likewise, the rock is made from aragonite. Years ago, when I began keeping reef aquariums, “live rock” was collected from coral reefs around the world. It consisted of broken pieces of the actual coral reef that were dislodged during storms. The rock was covered with coral reef species, often even corals, and provided a lot of plant and animal diversity. Because of the pressures on reefs, live rock collection was banned, and now live rock is cultured mainly by making limestone rocks and putting them in the ocean near coral reefs for extended periods of time and allowing them to become colonized by other species. With real “live rock” - that is chunks of unconsolidated reef framework -extensive denitrification occurs in hypoxic and anoxic areas that depends on the variable porosity of the rock. But, now that live rock largely consists of variously prepared cementitious materials and despite having visible holes, nooks and crannies, is inherently dense in areas where denitrification would occur. In fact, having cut many types of “cultured” live rock, there is very little functional area for denitrification and seems to serve largely as a surface veneer for colonization.

Once rock, sand and water are in the new aquarium, and the tank is being fed, the first visible signs of rapidly increasing life will be algae. Algae tend to come in successional phases that last at least several months. Usually, golden brown diatoms will be first until they quickly deplete excess silicate in the water. There may also be blooms of cyanobacteria (that form green and red mats). These have a negative correlation with water flow and providing strong water flow will ameliorate or prevent cyanobacterial mat formation. These are frequently followed by dinoflagellates such as Chrysocystis fragilis, and soon after various types of turf algae. Some turfs are highly desirable as a food source for herbivorous crustaceans (amphipods, etc.), fish, and invertebrates (urchins, snails, etc.). Others can become problematic, notably Derbesia and Bryopsis spp. These tend to be unpalatable by most herbivores and are a common nusiance algae in reef aquariums. This is why the first inhabitants of a reef aquarium should be herbivores. Adequate herbivory using a diversity of herbivorous species in a tank is all it takes to permanently control all forms of nuisance algae, and conversely may make it difficult to cultivate desirable or “decorative” algae if desired without and area of herbivore exclusion (i.e. a refugium or sump compartment).

Also important initial additions are scavengers and detritovores – those species that feed on deposits and detritus that sink to the bottom and into the interstitial spaces of live rock. Serpent stars and brittle stars, as well as some snails (e.g. Nassarius sp.) that feed on detritus (particulate material consisting mostly of dead algal filaments, mucus, waste and coated in bacteria) are the “vacuum cleaners” of the reef aquarium.

It’s important to get through these successions without them becoming established or they continue to present problems in reef aquariums. In a few months after these successions have run their course, pretty red, purple and green crustose coralline algae begin to grow, and that’s when the tank is ready to thrive.

After the algae blooms, and perhaps during the first months, it may be good to add some corals to get them established. For example, Pachyclavularia/Briareum viridis (green star polyps) – I put a slash with the genus because despite the fact they are found by the thousands in aquariums all over the world and are very common of coral reefs, scientists are still not sure of the taxonomy - are very hardy and are a test species for me to evaluate the tank. This coral is an octocoral (aka soft coral) that consists of bright green interconnected polyps extending outwards from a rubbery purple mat of stolons. They will grow outwards, encrusting the rock. This coral survives and grows so well, it sometimes can overtake almost everything else in the tank, and an aquarist should be careful to not let it do that!!

Corals should then be added, as appropriate to the habitat being recreated in the aquarium. Care of individual corals is covered later, but slow additions are a good idea to determine what species are adaptable to the conditions of the aquarium. They should be allowed to grow and establish because they provide the habitat for the majority of coral reef species, including fish. Once the tank is then stable with growing corals, it is time to invite fish into their new home that is now a low stress environment with all the appearance and many of the diversity of species from which they came. Having adequate places to inhabit, shelter and hide as they become accustomed to their environment, already having stable water quality and having had food provided for many months makes fish loss and disease prevalence greatly reduced. It must be forewarned, however, that ALL new additions must be properly quarantined prior to addition and that topic is covered in the next section.

I recognize that the order of introduction is contrary to much existing knowledge, but it is the way it happens following a disturbance on reefs and the natural ecology and succession of species on the reef. The idea of using bacteria to make seawater nontoxic of ammonia and immediately adding hardy fish is both wrong and stressful. I recognize this method requires patience – something not in abundance when starting a tank – but watching these processes and the development of copious life prior to fish – some of which can decimate as yet unestablished populations in the tank – will contribute to a more fulfilling experience and long terms successful husbandry.

Collections

View all-

Staff picks from $20 and below!

Frag out of control with this awesome deal! All frags in this...

-

Phytoplankton, Macro Algae, & More!

Enhance your reef tank with our selection of live phytoplankton, macroalgae, and...

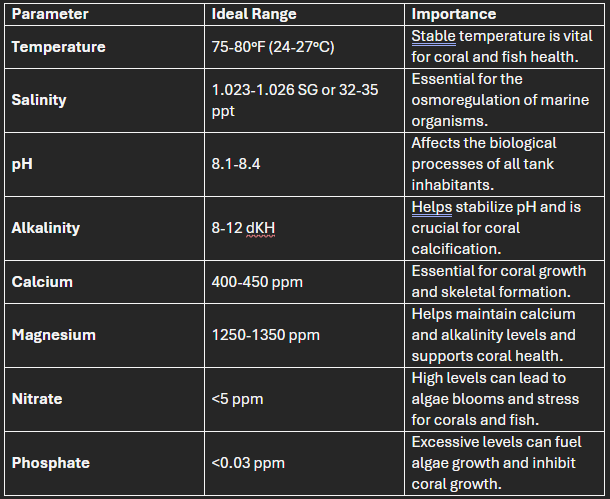

Water Parameters

This chart should help you keep track of the essential water parameters for your reef tank. If you need any more details or have other questions, feel free to ask!